Cooksonia, a very old land plant (II)

(I)

The presence

of xylem vessels with annular or spiral-shaped thickenings at the walls counts

as characteristic for higher plants. Algae and mosses do not have such

tracheids. The presence

of xylem vessels with annular or spiral-shaped thickenings at the walls counts

as characteristic for higher plants. Algae and mosses do not have such

tracheids.

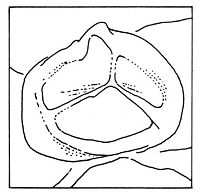

Several stems of Cooksonia show a central black line or thickening,

which is probably the remainder of a xylem strand.

D. Edwards (1992) was the first one to publish photos of xylem vessels of

Cooksonia (Photo with permission of Nature Publishing Group). Edwards

found the tracheids in axes with attached sporangia of the species C.

hemisphaerica en C. pertoni from Lower Devonian river sediments

in

Shropshire.

D. Edwards (1992) was the first one to publish photos of xylem vessels of

Cooksonia (Photo with permission of Nature Publishing Group). Edwards

found the tracheids in axes with attached sporangia of the species C.

hemisphaerica en C. pertoni from Lower Devonian river sediments

in

Shropshire.

Yet there are several snags in the assumption that every plant of

Cooksonia had tracheids. In the first place no tracheids have been

found in Silurian Cooksonia fossils. So it is possible that the tracheids

developed only in the course of time.

Secondly it has been discovered with the use of electron microscopy that

in different species of Lower Devonian plants two kinds of strengthened 'xylem'

strands occurred. One of those appears to be related to the central strands

of mosses ...

Tentatively it is assumed that the oldest Cooksonia's were also

in the possession of tracheids.

Spores

In

most cases no spores are present in the sporangia. Sometimes they have been

preserved, but as a heavily compressed mass in which the individual spores

can hardly be distinguised. Only very seldom have they been preserved in

a rather good, threedimensional form. On the right hand side a drawing after

a SEM-photo of a spore of C. pertoni (diameter 30µms; drawing

J. Hulst). In

most cases no spores are present in the sporangia. Sometimes they have been

preserved, but as a heavily compressed mass in which the individual spores

can hardly be distinguised. Only very seldom have they been preserved in

a rather good, threedimensional form. On the right hand side a drawing after

a SEM-photo of a spore of C. pertoni (diameter 30µms; drawing

J. Hulst).

Research on spores of C. pertoni from different places in Great

Britain has revealed an evolutionary trend. The existence of four different

types of spores in C. pertoni has been proved: two are common and

two rare. There appears to be a tendency from smooth spores in the Silurian

to more ornamented ones in the Early Devonian. Of course the advantage of

ornamented spores for the plant remains uncertain, but it could possibly

be an adaptation to drought.

Comparable smooth spores have been found in the Lower Silurian. Though the

oldest known Cooksonia-fossils are of

Mid-Silurian age, this could point to an even

earlier occurrence of Cooksonia or other plants.

Occurrences

The oldest Cooksonia-fossils have been found in Ireland. They date

from the Late-Wenlock (425 million

years). The preservation is not good enough to identify them at species name,

but they are clearly Cooksonia-like plants with sporangia. Axes without

sporangia are also found, some of them with up to three branchings.

Somewhat

younger Cooksonia-fossils have been found in North-Wales, at a locality

in the Lower Ludlow (420 million years). These

fossils are diminutive. My biggest fossil from this place is a branchlet

with two bifurcations measuring 15 mms. Axes like these are sometimes placed

in the artificial genus Hostinella. Some of the axes show a black

line, probably pointing at the presence of xylem vessels. Somewhat

younger Cooksonia-fossils have been found in North-Wales, at a locality

in the Lower Ludlow (420 million years). These

fossils are diminutive. My biggest fossil from this place is a branchlet

with two bifurcations measuring 15 mms. Axes like these are sometimes placed

in the artificial genus Hostinella. Some of the axes show a black

line, probably pointing at the presence of xylem vessels.

Silurian Cooksonia-fossils have also been found at some other places

in Wales and Shropshire. Edwards even found all four from Great Britain described

species at one locality on the South coast of Wales.

Outside Great Britain Silurian Cooksonia-fossils have been found

in Canada (not identifiable at species name) , Bolivia (resembles C.

caledonica), Czech Republic (C. hemisphaerica), Kazakhstan (not

identifiable), China (the same), Siberia (C. pertoni, C.

hemisphaerica), the state of New York (not yet identified) and perhaps

in Libya.

C. paranenis from Brazil is dated as uppermost Silurian or lowermost

Devonian. This last find demonstrates the occurrence of Cooksonia

at a considerable shale in parts of the large southern continent Gondwana.

Cooksonia also occurs in younger deposits. C. caledonica

has been described on the basis of Lower Devonian fossils from the area

around Forfar (Scotland).

River deposits from the Lower Devonian of England have yielded fragmentary,

but extremely well preserved fossils of all British species of

Cooksonia. Detailed studies could be made of the structure of the

sporangia and the spores of these fossils.

Recently a new species, C. banksii, has been described from this locality,

which resembles very much the Brasilian Cooksonia (Habgood et al,

2002).

Way of growing

It

is striking that most of the sediments containing Cooksonia are marine ones.

Probably the plant grew at plains along the rivers which became submerged

from time to time. Stems of the plants were then broken off, transported

and buried in the sediments on the bottom of the sea. This could explain

why roots or horizontally growing stems (rhizomes) have

never been found until now. Cooksonia was likely to have rhizomes,

for another early plant, Rhynia, related to Cooksonia, was

attached to the soil in that way. The horizontally growing stems of this

species developed root hairs at places where the stems touched the ground.

Perhaps the strange branching at the right hand side could be a rhizome.

That would be a major find! It

is striking that most of the sediments containing Cooksonia are marine ones.

Probably the plant grew at plains along the rivers which became submerged

from time to time. Stems of the plants were then broken off, transported

and buried in the sediments on the bottom of the sea. This could explain

why roots or horizontally growing stems (rhizomes) have

never been found until now. Cooksonia was likely to have rhizomes,

for another early plant, Rhynia, related to Cooksonia, was

attached to the soil in that way. The horizontally growing stems of this

species developed root hairs at places where the stems touched the ground.

Perhaps the strange branching at the right hand side could be a rhizome.

That would be a major find!

Salt marshes have also been mentioned as possible growing places for

Cooksonia.

It is furthermore likely that the plants were growing in vegetations existing

of only one species. Most of the Early Devonian plants were also living in

such monospecific vegetations.

The Brazilian C. paranensis grew in an area not far from the South

Pole at that time under probably rather extreme circumstances. Though the

flora indicates an ice-free environment, the sunken sporangia appear to be

an adaptation to low temperatures.

Cooksonia probably grew as a small shrub.

Top

|